Why Intelligence Doesn’t Improve Reasoning

Why real-world rationality is not a matter of IQ, but of timing, framing, & incentives.

What does it mean to be ‘logical’?

I remember when I first took Introduction to Logic in college. The course covered propositional and predicate logic, Aristotelian logic, problems of definition, informal fallacies, and basic linguistic analysis. It was notoriously disliked by many students, but I loved it. It was satisfying to work through formal proofs that closely resembled the way I already thought about problems.

One day, I asked another student why so many students considered logic very “hard.” She replied that there were people who “got” logic and people who didn’t. Those who struggled with logic often relied on attending homework help sessions with Teaching Assistants (TAs) to pass the class. The TAs were former students for whom the material had simply “clicked.”

Instantly, I became curious about the TAs. It was my first semester, and I had struggled to make friends. I thought it might be easier to befriend people who naturally shared my preference for formal systems. So, I went to a homework help session solely to meet the TAs. As expected, they could produce twenty-step proofs almost automatically. They understood logic well. Many were also skilled at math.

My hopes may have been high to begin with, but I was surprised by what followed. After interacting with the logic TAs in clubs and other classes, I noticed that they were no more careful or disciplined reasoners outside of formal logic than any other students. Most seemed to be average at critical thinking. Shockingly, some even struggled to write philosophy essays. Others did not seem especially analytical, insightful, or curious, though this did not appear to be a matter of intelligence.

This puzzled me. These students clearly understood deduction and formal reasoning. Why didn’t their rationality in handling formal proofs carry over into other contexts? Why weren’t they any more epistemically reliable when evaluating claims outside a problem set?

Soon, I had a revelation. The answer, I thought, is that they know to enter a deductive reasoning mode when presented with a proof. But when they’re outside of the classroom, they do not recognize the regular claims they encounter on a daily basis as requiring evaluation. The proof prompts them to reason, but most regular claims don’t.

It also seemed to explain why I remained logical both inside and outside the classroom. Even though these TAs were just as good at formal logic as I was, they did not share my tendency to apply systematic reasoning to everyday situations. Their reasoning was context-bound; mine seemed borderless. Surely, my autistic thinking process and tendency to systematize gave me a clear advantage. I figured I was more of a reasoning “generalist.”

It turns out I was right that many people fail because they do not recognize when reasoning is required, and therefore never enter an evaluative state at all.

But my confidence turned out to be a bit misplaced. I had thought that my lifelong inclination to treat real-life situations like logic problems put me far ahead of those who don’t even know when to apply reason much at all.

In reality, the people who are naturally more prone to thinking strategically and logically—including systematizers, academic experts, policy analysts, and high-IQ individuals—are actually not inherently better at reasoning effectively. They fail for different reasons.

Most people aren’t bad at reasoning. They’re bad at knowing when to reason.

Most people are not incapable of reasoning. In fact, they reason fairly well in certain situations. The problem is that those situations are narrower than we tend to admit.

People reason best when the environment makes it obvious that reasoning is required. This usually means there is a clear cue that something is a “thinking task,” some expectation of challenge or evaluation, and some consequence for being wrong. My logic class reflected this. When people expect to be challenged, graded, or corrected—especially by a strong opponent—they check their assumptions and think more carefully.

People also reason better when given fast and unambiguous feedback. For example, games, programming, and some financial decisions punish error quickly and visibly. Seeing consequences to your mistakes improves your reasoning. When feedback is delayed, vague, or socially filtered, your reasoning degrades.

Incentives play a big role. People reason better when rewarded for accuracy over conformity. This is why some scientific collaborations and forecasting tournaments outperform everyday discourse. This is why we should strive to create institutional environments that allow dissent without the risk of hurting one’s reputation or social status. In contrast, when beliefs signal moral virtue, political loyalty, or group membership, people get defensive and reason poorly—becoming more incentivized to stay aligned with their group than be correct. This is why people are better at reasoning when it comes to neutral topics, like chess, rather than identity-based topics.

Finally, people are better at spotting flaws in someone else’s argument than in their own. This asymmetry is strong and well documented. Dan Sperber and Hugo Mercier’s Argumentative Theory, which posits that human reason developed to persuade others and justify one’s own beliefs, explains why we’re prone to “my-side bias.” It also explains why group reasoning may improve outcomes.

Why don’t people recognize when they should reason?

If people are capable of reasoning, the obvious question is why they so often fail to notice when reasoning is required.

In everyday life, it is usually easier and more practical to rely on shortcuts like trust, authority, or general impressions than to scrutinize claims in detail. If someone runs out of a building yelling “fire,” you’re not going to stop to evaluate their evidence—you’re going to leave. Constant evaluation would be exhausting, and unnecessary in many cases.

The problem is that many claims are presented in ways that mimic these low-scrutiny contexts. Claims are often disguised as background information, common sense, or shared understanding rather than as assertions to be evaluated. This prevents people from questioning the claims.

Skilled communicators don’t need to persuade by making obviously false claims. Rather, they can shape judgment by embedding assumptions into the situation being described. They treat certain premises as given: what the problem is, what caused it, which considerations matter, and which responses are “serious.” By the time people start to disagree, they’re doing so within the frame. They’ve already accepted those assumptions as context rather than claims, no evidence or rationale required.

I frequently see narratives exploit this weakness, introducing claims in ways that fail to trigger scrutiny, even among people who are otherwise capable of careful reasoning. Sometimes the narrative clearly fills a “tribal cohesion/mimetic scapegoat” function, and has not even established a causal mechanism—and already, even people who have good reason to disagree with it are arguing against it within the frame, unknowingly giving legitimacy to assumptions they should’ve challenged.

Now, normally, here’s where I’d be thinking: Sounds about right for most people. But not me. If delaying reasoning is supposed to be more efficient, my brain missed the memo. The faintest whiff of a claim is enough to make me start reasoning right away—often to an annoying degree, sometimes accompanied by a barrage of questions or objections. No claim is too covert or minor for me to challenge. If most people wait too long, that must mean I’m safely on the other side of the error. Right?

Well, this is where the story gets less reassuring. The people most confident that they reason early and often—high-IQ individuals, policy analysts, and theorists—turn out to fail in a different way.

1. Why high-IQ individuals fail at reasoning

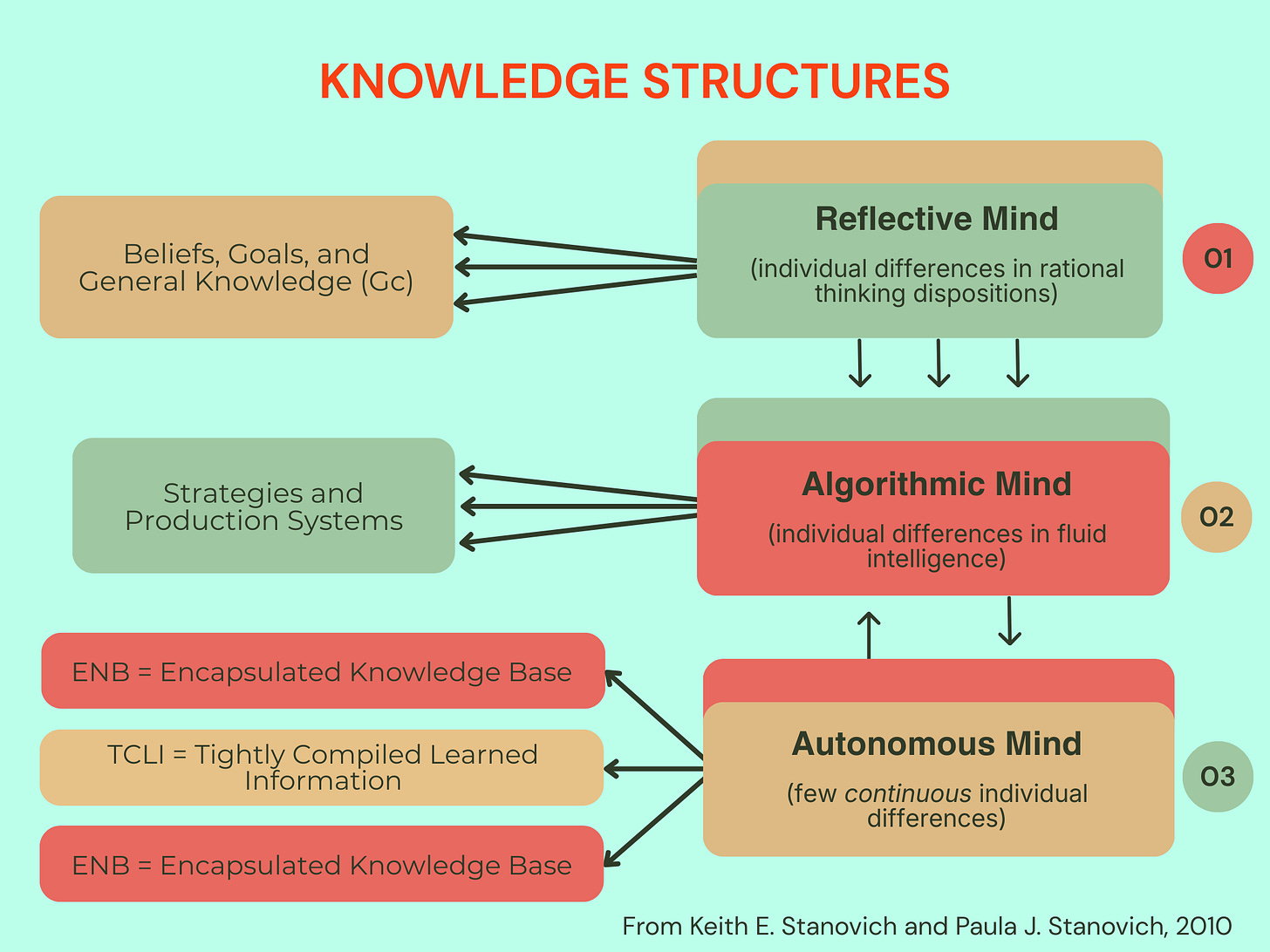

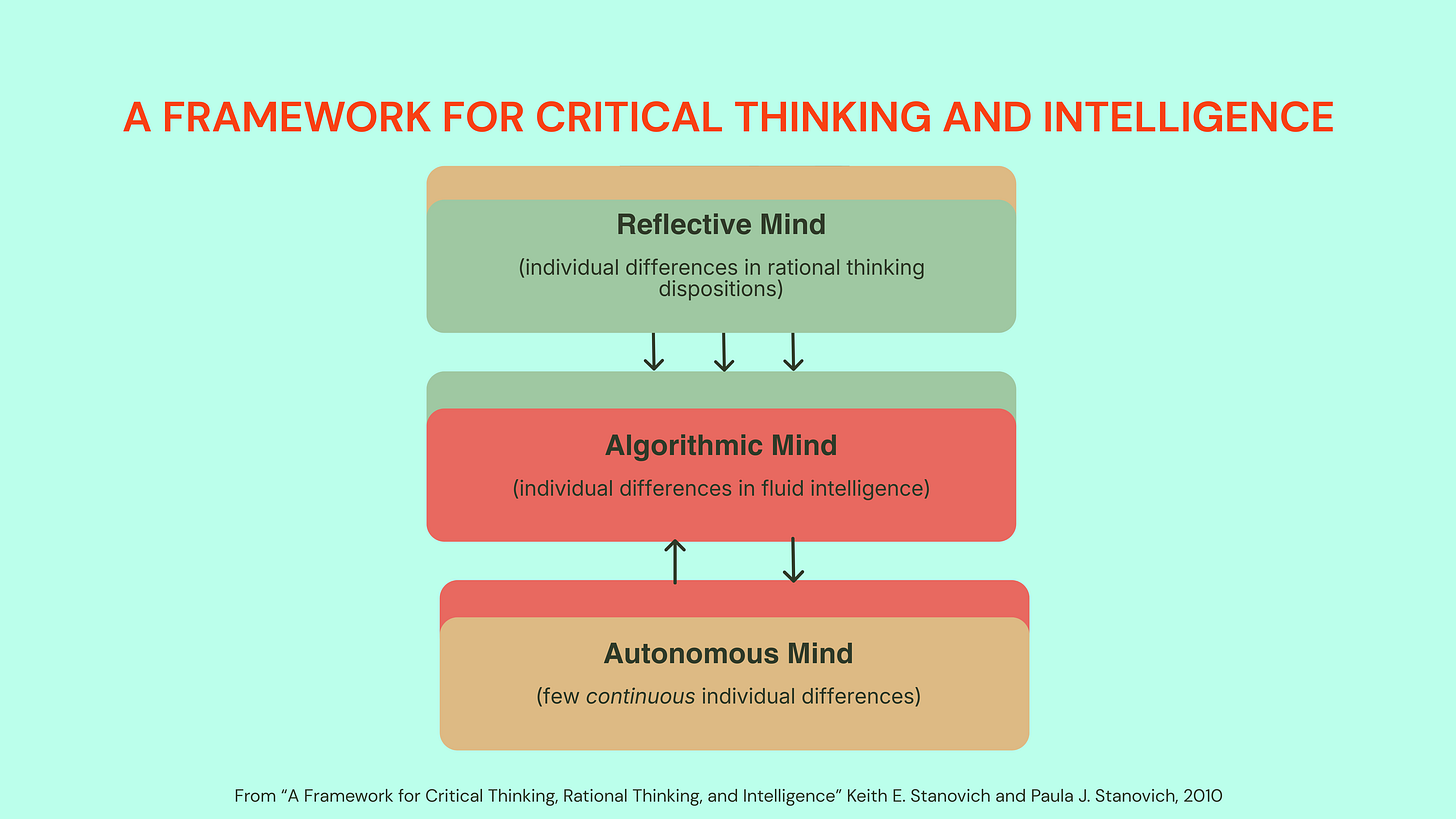

High intelligence, as measured by IQ, is associated with stronger performance on tasks that require abstraction, working memory, pattern detection, and error correction. People with higher IQ tend to perform very well on clearly defined formal reasoning tasks, such as logic problems, mathematical proofs, and other situations with explicit rules and success criteria. Being very intelligent improves how efficiently you can execute reasoning after initiating analysis. In short, IQ helps with what Keith Stanovich calls algorithmic processing.

High IQ does not, however, reliably increase rationality.

Keith Stanovich’s work on the intelligence–rationality distinction shows that dispositions such as actively open-minded thinking, willingness to consider alternatives, and willingness to delay closure are only weakly correlated with IQ, despite being crucial for sound judgment outside formal tasks. These “thinking dispositions” predict real-world epistemic outcomes better than intelligence alone.

Stanovich explains that IQ tests don’t measure rationality because they fail to assess the “macro-level strategizing” or “epistemic regulation” that is essential to one’s rationality. IQ tests eliminate or reduce the need for the “reflective mind” by clearly alerting test-takers that they need to use algorithmic reasoning.

In contrast, real-world reasoning problems rarely come with such cues. A person can fail either by never entering an evaluative mode or by reasoning fluently toward the wrong target. IQ primarily improves execution once reasoning has already been engaged; it does not determine when to engage it, what assumptions to question, or whether to step back and reconsider the overall frame.

Thus, a “rationality” test would need to be less explicitly labeled, so that the test-taker could fail in two ways: by making an error in algorithmic reasoning, or by failing to recognize the need for algorithmic reasoning.

2. Professional analysts’ judgment also fails

Political psychologist Philip Tetlock’s long-term studies of expert judgment show what this looks like in practice. Many of his participants were highly intelligent, well-educated generalist policy analysts and commentators. They constructed coherent, theory-driven explanations of political and economic events, and they were often very good at maintaining internal consistency within those explanations.

The surprising result was that these same strengths made it harder for them to abandon faulty frameworks. When new information showed their forecasts to be wrong, theory-committed thinkers tended to revise individual claims or auxiliary explanations rather than reconsider the underlying model. Thus, they ended up missing fundamental errors.

Taken together, these findings show that higher intelligence helps people carry out reasoning tasks efficiently, but it does not ensure their reasoning is aimed at the right problem. Smart people can be better at defending explanations, but if they lack the right dispositions needed to step back and question their assumptions, they become more confident and persistent in their reasoning without becoming more accurate.

3. How fact checkers beat experts at both failure modes

We often trust people who are experts in a given field to be the best at evaluating the veracity of claims in that field. But who do you think is better at determining the accuracy of historical claims found online: tenured history professors with subject-matter expertise, or professional fact-checkers with no specialized background in history?

Empirically, it is the fact-checkers.

In controlled studies comparing how different groups assess online information, professional fact-checkers consistently outperform professors, including historians trained to evaluate sources for a living. It has little to do with one’s intelligence level or depth of knowledge, and simply comes down to a different set of protocols being followed.

As documented by Sam Wineburg and Sarah McGrew in Evaluating Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning, fact-checkers begin by classifying the situation before engaging the content. They leave the page immediately, search for more context externally, and establish whether the source itself warrants attention. Only then do they decide whether close analysis is appropriate. (For a stripped-down version of this approach, check out digital literacy expert Mike Caulfield’s SIFT method.)

Professors tend to do the opposite, remaining on the page and analyzing the argument as presented.

The fact-checkers don’t beat the professors by thinking harder, spending more time reading, or having more historical knowledge. Rather, they simply delayed claim analysis long enough to establish the right constraints. This delay protected them from both failure modes described earlier: never entering evaluation at all (the common mode of failure for most people), and entering it too quickly inside an unexamined frame (the common mode of failure for smart people).

4. Are high-functioning autists better at reasoning?

Okay, now I had to address autism, because having the Asperger’s profile of autism definitely seemed to be the main factor behind my more “logical” disposition. It is tempting to think that people with high-functioning autism/Asperger’s are better at reasoning. After all, autists’ brains are wired differently; they generally process things less intuitively, and have to actively think through situations daily that other people don’t have to consciously think about.

Like many other high-functioning autists, I’ve always been seen as more “logical,” “rational,” and “good at critical thinking.” I tend to pursue facts relentlessly and often care more about understanding what’s true than about fitting in or pleasing people. That does give me some advantages. And it’s true that just as people with high IQ have advantages when it comes to reasoning, so do people with high-functioning autism.

Many autistic people rely less on social consensus when evaluating claims. Autistic people are also less likely to defer automatically to prestige or authority, and often less sensitive to implied meaning, rhetorical suggestion, or emotional framing. In practice, this can make certain misleading narratives less effective, especially those that rely on “vibes”, outrage, or status cues.

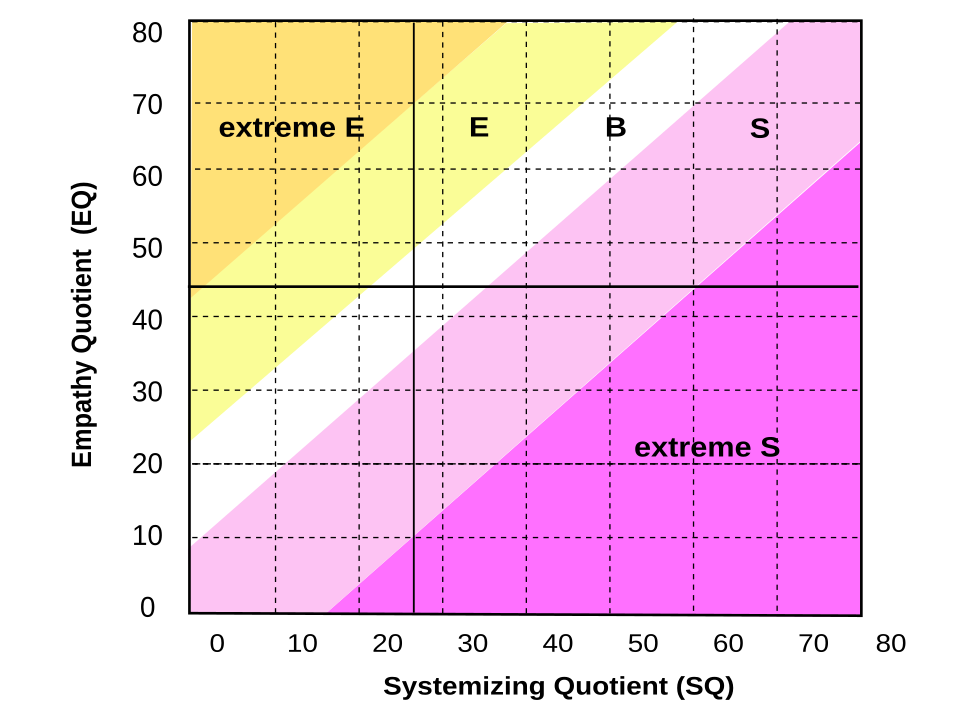

Systematizing adds another layer. According to Simon Baron-Cohen’s Empathizing–Systemizing theory, autistic cognition is often characterized by a strong drive to identify rules, regularities, and lawful structure. This is extremely useful in domains with stable rules and clear feedback—math, engineering, programming, the hard sciences. Systematizing makes you good at maintaining internal consistency and refining a model once it exists.

But this is also where the failure mode appears. Baron-Cohen explicitly notes that when a system is internally coherent but poorly constrained by external reality, high systemizers tend to keep refining it rather than questioning its premises. This is framed as misapplied rationality. Evaluation focuses on internal consistency rather than on whether the system is actually tracking the world.

Autism research often describes this as strong local reasoning paired with “weak central coherence.” This means being very good at detecting patterns and inconsistencies in parts of a system while missing broader contextual constraints. In political or narrative domains, this can produce elaborate, elegant explanatory frameworks that are logically tight but selectively framed, distorting or omitting crucial context.

This matters because propaganda, ideology, and information warfare often work through framing, salience, and omission. A model can be perfectly consistent and still be built on a filtered slice of reality.

Finally, many autistic people have a strong aversion to uncertainty. Under ambiguity, this can push them toward rigid or dichotomous reasoning. Because the resulting explanation is coherent and well-defended, it can sound especially convincing to people who are less inclined to reason. That asymmetry makes errors harder to interrupt—both for the systematizer and for everyone else.

We all have biases in our thinking, and one way to get better at reasoning is to practice the traits that improve our reasoning—like curiosity and humility. Instead of being ashamed of our errors in reasoning, we should reflect on them and see them as learning opportunities.

For example, I recently realized that if I find a topic very uninteresting, obvious, or simple, I might not spend much time reading about it at all. I sometimes get more preoccupied with the challenge of learning things I didn’t already know and piecing them together, that I don’t stop to think about more obvious knowledge. By making things more challenging and fun for myself, I can end up neglecting simple, relevant facts that would’ve prompted me to reconsider my assumptions.

Conclusion: Why intelligence alone isn’t the fix

RATIONALITY CAN BE LEARNED AND IRRATIONALITY AMELIORATED One of the things that we are missing is a focus on the malleability of rationality. […] People make many suboptimal decisions because of the failure to flesh out all the possible options in a situation, yet the disjunctive mental tendency is not computationally expensive. […] This is consistent with the finding that there are not strong intelligence-related limitations on the ability to think disjunctively and with evidence indicating that disjunctive reasoning is a rational thinking strategy that can be taught.

—Keith E. Stanovich, A Framework for Critical Thinking, Rational Thinking

Most people already understand, at least intuitively, that high intelligence does not guarantee good judgment. We all know smart people who believe strange things. What is less discussed is why this happens so reliably, and what we can do to improve rationality.

Knowing that the problem comes down to recognizing when to reason and what to aim reasoning at explains why simply “increasing intelligence” does not solve epistemic problems. In fact, there are often stronger incentives for highly intelligent people to use their reasoning abilities to defend accepted narrative frames than to challenge those frames and ask whether they are true.

We are surrounded by systems that decide what appears credible, settled, or worth questioning before we ever encounter a claim. Algorithms surface some narratives and bury others. Social incentives determine whether skepticism comes across as principled or disloyal. Trust in institutions has declined, and there are fewer internet gatekeepers. Under these conditions, the most internally coherent and emotionally evocative explanations often win, because nothing interrupts them. Bad ideas spread quickly and reach many minds—minds that are capable of reasoning, but not at the right level or at the right time.

In information operations and cybersecurity, it is well understood that human cognition is the primary terrain. I find it strange that this is treated as common knowledge in those fields, yet rarely motivates a serious effort to teach people concrete protocols for reasoning under real-world conditions, or create better incentives for dispositions that improve reasoning.

I don’t agree with cynics who say reasoning is futile. It is fragile. Intelligence does not protect it. Incentives and procedures might. It’s acknowledged in IO. Why do we still not treat it as a public priority?

And as always, feel free to leave a comment. I welcome your thoughts, critiques, and disagreement.

This is all fascinating. I am very glad to have discovered you.

Right on point. It would be interesting to research why people by default get so attached to their existing beliefs/hypothesis even when putting aside social incentives (social alignment/reputation/self-interest/identity/etc). People seem to get emotionally attached to their priors and it feels painful to discard them.